Chinese Carpet

Chinese Carpet or Chinese Rug is one of the eastern rugs that woven in China.

Rugs of China are considered to include those of Manchuria, Mongolia, and Xinjiang. Rugs were primarily woven in northern China. A Chinese saddle blanket from Lop Sanpra was dated to about 100 b.c.e. A few pile rugs have been dated to the Ming dynasty. Domestic pile rug production in China was quite small until production for export began in about 1890. Rug-weaving centers predating rug production for export include Ningxia, Baotou, Suiyuan, and the towns of Gansu.

Commercial rug production for export began late in the nineteenth century in Beijing and about the turn of the century in Tianjin. Tianjin became the center of large-scale commercial production from about 1910 to 1930 as foreign firms came to dominate the Chinese rug industry. American firms in China included Karagheusin, A. Beshar & Co., Donchian, Avanosian, Kent-Costikyan, Elbrook Inc., Nichols Super Yarn, and Fette-Li. Throughout the early twentieth century, the United States was the largest importer of Chinese rugs. The peak period of rug production and shipment to the United States was 1925. In the early 1930s, rug production was interrupted by the Japanese invasion. Large-scale commercial production was not resumed until the 1960s.

Chinese rugs use the asymmetric knot with occasional use of the symmetric knot in edges and ends of early examples. Chinese rugs are not finely knotted, varying between 30 and 120 knots per square inch. Some early Chinese rugs have asymmetric knots that are offset on warps or skip warps at curving borders of color changes. Early rugs have no warp offset, while later rugs have offset warps, some with closed backs.

Contemporary Chinese rugs are woven in cooperative factories. There is consistent quality in these rugs due to the use of steel looms, chrome dyes, and objective production standards. The "line" is the contemporary measure of knot density. Woolen carpets are woven in 70, 80, 90, and 120-line qualities. Silk rugs are woven in 120 to 300-line qualities. Pile heights for wool rugs are ⅜, ½, and ⅝ inch. The pile height for silk rugs is ½ inch. The Chinese rug trade designation "Super" means a 90-line rug with ⅝ inch pile height and a closed back.[1]

| Chinese Carpet | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Name | Chinese Carpet |

| Original name | فرش چین، قالی چین |

| Alternative name(s) | Chinese Rug |

| Origin | |

| Technical information | |

| Common designs | Medallion |

| Pile material | Wool, Silk |

| Foundation material | Cotton, Silk |

| Knot type | Asymmetrical (Persian), Symmetrical (Turkish) |

History

China is a country in East Asia and an ancient civilization with a strong cultural and artistic identity that dates back over four millennia. In 2640 BCE the silkworm was first cultivated and exclusively owned in China by royal and noble women. After several centuries the valuable commodity of silk was employed in garment weaving, which revolutionized trading within China. The historic Silk Road was built under the Han Dynasty, which reigned from 206 BCE to 220 CE and advanced China by enabling trade with the Middle East and Europe.

Recent excavations in western China have uncovered rugs from the second century BCE. Knotted pile carpets from China made as early as the sixteenth century are known in the market. Pile carpets were developed early in the Tibetan region of southwestern China, and Tibetan weavers are credited with introducing rug-making techniques and designs to mainland China. During the latter part of the Ming Dynasty (mid-sixteenth to mid-seventeenth century), a group of Imperial carpets was made for the Forbidden City palaces, several of which are preserved in the Palace Museum of Beijing. These carpets were woven in large dimensions for the royal court. There is debate surrounding where they were made, but it is believed they were woven in a Beijing workshop or in Ningxia, in western China.

Notable weaving centers in China were based in Baotou, Kansu, Ningxia, Peking, and Tientsin. The historical eastern Turkestan cities of Kashgar, Khotan, and Yarkand, which produced popular carpets starting in the seventeenth century, were annexed by China in 1884.

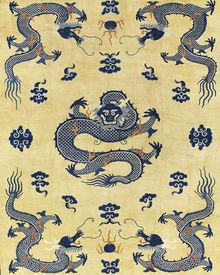

Early Chinese carpets are simple in design and perfectly drawn. The motifs were strongly influenced by Buddhism and were commonly painted on decorative objects, especially ceramics. The carpets were made for daily use or pillar decorations in temples and palaces. Early Chinese carpets have a cotton or silk foundation and a wool pile. Rare examples of silk pile carpets are found in the antique trade and at auction. The Persian (asymmetric) knot was always employed. The designs were woven in medallion or allover styles. Some carpets were made with several medallions in the field with a circular or moon-shaped design. The motifs applied in the carpet background feature flowers, lotus, leaves and vines, lion-dogs, birds, landscape scenery, yin and yang, clouds, butterflies, animals, dragons, mountains, falcons, phoenixes, little houses, shou motifs, vases, good luck knots, swastikas, and frets, among others. The main and inner borders feature patterns such as sea waves, pearls, Greek keys, flowers with leaves and vines, and traditional Chinese motifs.

Early Chinese carpets are charming in design and coloration and are regarded as an art form in the antique market. They are in demand by collectors and consumers, who are willing to pay high prices to obtain them.

By the nineteenth century pieces with flower designs in the field were starting to be made in eastern China for export. Chinese carpets were fashionable in the Western markets during this period because the modest and delicately drawn flower motifs and the use of just three or four colors in the overall carpet coordinated well with the decor of American households. These famous weavings are called "Peking Chinese" carpets in the antique market. The background coloration is mostly ivory, light blue, or dark blue. These three colors were also commonly woven in the borders and design elements, which is a noticeable characteristic of the Peking style. They have a plain-colored outer border, which can reach up to three inches in width. Carpets made in this period had a cotton foundation and a wool pile.

A second important group of carpets is called "Art Deco Chinese". They were produced in China during the 1920s and 1930s and were popular in the American market. These carpets have a cotton foundation made with heavily pounded wefts and a high wool pile. The designs have an Open Field style featuring mostly flowers, blossoming branches, little houses, or vases in one or two corners of the carpet; at times birds or butterflies are included. Art Deco Chinese carpets have three distinct characteristics. First and most important, they feature many different and unique designs that were rarely duplicated in other carpet-making centers. Second is the variety of colors chosen for the background and borders, such as pink, orange, brown, cinnamon, maroon, and yellow, and many others. The third characteristic is that the rugs were durable and heavy to handle. Art Deco Chinese carpets were manufactured by American entrepreneur Walter Abner Burns Nichols (1885-1960) under his firm Nichols Carpets, mostly in northeastern China. In the antique market Art Deco Chinese carpets are also called "Nichols Chinese" by carpet dealers.

During the 1920s another type of carpet was made in eastern China for the American market under the direction of Helen Fette, known in the trade as "Fette Chinese". An American and one-time missionary in China, Fette joined Chinese carpet manufacturer Li Meng Shu to start the Fette-Li Company, based in Peking. The carpet designs are floral with mostly open-field styles and simple motifs such as vases, flowers, floral bouquets, blossoming branches, birds, and butterflies. The carpets had fine, shiny wool with a high pile. Fette-Li productions were woven with a lighter foundation technique than their competition, Nichols Chinese carpets. Fette Chinese coloration found in the trade is mostly pastel compared with Nichols weavings. The coloration of Fette carpets found in the old rug market is mostly maroon, ivory, or dark and light blues for the field and border. In addition to these colors, green, yellow, brown, black, gray, pink, lavender, and turquoise were included for design motifs, and, occasionally, for the background and borders.

In the 1960s China began to produce a new line of carpets with shiny wool and a high pile. A popular design was the French Savonnerie Carpets style, which was fashionable in the American market. Weavers trimmed around flower motifs to make the designs stand out and be charming in appearance. These carpets were marketed by their different qualities, and were called "70 line", "90 line", and "120 line" Chinese carpets. The line count represents the number of knots in a linear foot; the higher the number, the better the quality.

By the last quarter of the twentieth century the People's Republic of China opened up trade to the world market, and carpet production grew substantially throughout the country. Many towns and cities began manufacturing carpets on a large scale in addition to the historical weaving centers, thus making China the largest Oriental carpet exporter in the world. During this period China duplicated the weaving techniques along with popular floral and geometric patterns developed from other weaving countries, such as Iran, Turkey, India, the Caucasus region, France, and England. Notable carpet designs employed in Chinese weaving centers are classical Persian, Turkish Hereke, and the Savonnerie and flatwoven Aubusson Carpets from France. Dealers in North America and Europe ordered these products and successfully marketed them because of their beauty and low production costs. These Chinese carpets range from medium to extremely fine in grade quality. They are woven either with a cotton or silk foundation and a wool or silk pile.[2]

References

Bibliography

- Abraham Levi Moheban. 2015. The Encyclopedia of Antique Carpets: Twenty-Five Centuries of Weaving. NewYork: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Peter F. Stone. 2013. Oriental Rugs: An Illustrated Lexicon of Motifs, Materials, and Origins. North Clarendon: Tuttle.